|

In Threes

Humans have always had a fascination with threes --- a fact I attribute to that very basic family unit (mom, dad, kid) --- and I’m struck today by the passing of three sports icons in the last three weeks. Bill Walton (May 27th), Jerry West (June 12th), and Willie Mays (June 18th) were athletes who transcended their athletic prowess to become cultural icons. My memories of each are from several perspectives--- as an athlete, as a fan, as a coach, as a teacher. Mays and West were the All-Stars of my youth when my passion for sports was growing exponentially, and they represented the pinnacle of greatness. Walton came a bit later (my younger brother’s age), when, as a college basketball fan and aspiring high school hoops coach, Walton represented the combination of intellectual acuity and athletic excellence John Wooden’s teams epitomized. I had the good fortune to see each of these athlete’s when they were performing at their peak and what I think was most impressive about each was not that they were capable of executing draw-dropping moments right before your eyes --- but that they performed at such a high-level of superb excellence that it was their norm. Not only that, they continued, after their playing days, to have a larger-than-life impact on the world of sports and the greater society. Willie Mays never played on a team I rooted for, but I could never root against him. While New York, during the 1950s (when I was just learning to be a baseball fan), roiled over who was the greatest center fielder --- Willie, Mickey, or Duke --- even Yankee and Dodger fans, when pressed, would grudgingly agree that it was Mays. All three ended up in the Hall of Fame but Willie was clearly the best --- and not just statistically. As any real fan of the game knows, the statistics did not, in those days, measure those defensive abilities that Mays excelled at. Tracking deep fly balls in the alleys, throwing out runners trying to take an extra base, making impossible shoe-string grabs --- Mays was the best. And running the bases --- oh, my goodness. His signature cap-flying-off-his head sprints from first to third or second to home; his ability to steal bases or turn a single into a double and a double into a triple --- unsurpassed. And there were also those 24 All-Star game appearances and 12 Gold Glove awards. He’s remembered for his incredible catch in the 1954 World Series --- his back to home plate in the cavernous Polo Grounds --- not only catching the ball but turning and throwing the ball back in with such velocity and accuracy that Larry Doby couldn’t tag up and score from second base and the runner on first had to hold. The Giants went on to win that game in extra innings and sweep the World Series. What statistics don’t reveal is that Mays hit 660 home runs playing in that same cavernous Polo Grounds and then the inhospitable wind-swirling Candlestick Park, on the edge of San Francisco Bay. Or that Mays missed over 200 games in 1952 and 1953 while serving in the U.S. Army --- with an estimated 60 career more home runs (which would have surpassed Babe Ruth’s record 714) not hit, based on his career averages. But it was seeing Mays play that was the real thrill because he always played at full speed, top gear, 100% --- and with joy! Beyond that, he was the first Roberto Clemente Award winner, a testament to his contributions to the community. It’s probably too grandiose, but it does make me think of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar quote: “His life was gentle; and the elements So mixed in him, that Nature might stand up And say to all the world, THIS WAS A MAN!” Willie Mays, R.I.P. Similarly, Jerry West was far more than his statistics would tell --- so much so that his nickname was “Mr. Clutch,” and his silhouette is the NBA logo. That said, West was a 12-time All-NBA player and 14-time All-Star. He was on the All-NBA Defensive team five times and is still the only player named NBA Final MVP while playing on a losing team. Again, those are only statistics. As a boy I was more a Celtics fan than Knicks fan (the Knicks, in those years were perennial cellar-dwellers with only Richie Guerin and Johnny Green and Willie Naulls keeping them from total obscurity). The Celtics, with Bill Russell and Bob Cousy and Bill Sharman and the Jones Boys (Sam and K.C.) and John Havlicek and Tommy Heinsohn were a juggernaut led by Red Auerbach who were all about team play and defense first, which appealed to me. The NBA was not a presence on television in those days, except for the Finals. And West was in the Finals nine times --- losing eight. Basketball, of course, is the consummate team game, and West’s teams were beaten by the Russell-led Celtics and Red Holzman’s brilliant Knick teams (and, yes, my allegiance had shifted back to NYC in the late-Sixties) but not because of West. He averaged 30.5 points per game, shooting 46% (before the 3-point line existed) from the outside in the NBA Finals. Watching him, like watching Mays, was incredible --- he was incredibly quick, with and without the ball, and could stop on a dime and launch unerring jump shots from all over the court. “Steals” weren’t a statistic that was kept until his final year in the NBA --- a season where he only played 31 games because of a career-ending knee injury. In those 31 games, West had 81 steals! Again, he was always excellent so if he wasn’t necessarily having a great offensive night, he could still kill you on defense. But he never quite had the supporting cast to get him all the championship rings he deserved. He did, in his post-playing career, continue to make the NBA one of the “must-see-TV” sporting events of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. As a team executive, West built two separate Laker dynasties (the Showtime Team and the Shaq/Kobe three-peat squads) and then helped craft the Golden State rise to the top. Always a perfectionist, West was a tortured soul in many ways, but, despite his Finals record as a player, he was a winner and a role model. “Zeke from Cabin Creek” was the real thing, a kid from West Virginia who drove himself to become one of the greatest athletes of all time. Bill Walton was not only an incredible player on the basketball court but was also one of the most interesting personalities off of it. At the tail-end of John Wooden’s UCLA dynasty, Walton epitomized the fundamentally sound tenets of the coach’s approach to the game. In retirement, as a motivational speaker, Walton waxed poetic about Wooden and often quoted him at length --- reflecting how the coach’s philosophy had become ingrained in his own world view. Not that they didn’t clash a bit when he was a player at UCLA. Walton’s anti-war stance during the early Seventies provoked his coach’s disapproval --- but no disciplinary action (Wooden was too principled for that). Walton was also known as a huge Grateful Dead fan from early on (not my cup of tea but I appreciated his enthusiasm for the music), aligning himself with a group known for endless concerts featuring a wide variety of drug-use. With all that was Walton the player --- and what a player he was. Before injuries untracked his NBA career, Walton proved himself one of the great college players of all time (3-time National Player of the Year, 2 Time Final Four MVP, 2-time National Champion) and, ultimately, one of the great “might have been” NBA stars --- winning a championship and accolades early in his career (1977 NBA Champ & Finals MVP, 1978 NBA MVP) and then again (1986) after injuries had decimated his body (while winning the “6th Man of the Year” Award). After his playing days Walton became an omnipresent college and NBA broadcaster, known for his sense of humor, unfiltered comments, and undying promotion of the Grateful Dead. Beyond his professional life on the court and behind the microphone, Walton, like Willie Mays, was a genuine philanthropist and community activist. As close friend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar noted on his Substack after Walton’s passing: Whenever we were together at a gathering, he bloomed. His enthusiastic personality and sincere concern for others inspired everyone around him. I marveled that he was never afraid to express his unapologetic love of people. He had wanted to be more like me on the court, I wanted to be more like him off the court. (After his passing)My initial unhappiness and despair would have saddened him and he would have done everything in his considerable power to lighten my load, to cheer me up, to make me see the bright side. Knowing that a person like Bill existed—and that I was lucky enough to be his friend for so many years—actually does cheer me up. Knowing that Bill is still influencing me and will be a treasured part of my life until I’m the next to fall is the bright side. Despite my grief, there is much joy in knowing that Bill can still make me happy. And always will. In life, that is the only legacy that matters. In the case of all three of these people, who happened to be brilliant athletes, the genuine legacy is not only how they played the game but who they were, what they embodied. Mays’s ebullience, West’s perfectionism, Walton’s gregarious intelligence are the greater models we might emulate. Few of us can match their athletic brilliance but all of us can aspire to their intense commitment to creating a better place to live.

2 Comments

Memorial Day

and Patriotism v. Nationalism The Thursday before Memorial Day weekend we had the pleasure of seeing our granddaughter’s Third Grade class perform as a choir, treating their audience to an array of songs honoring Memorial Day, Flag Day, and the 4th of July. They started with The Star-Spangled Banner and proceeded to sing: Stars and Stripes Forever, All American Me and You, This Land is Your Land, You’re a Grand Old Flag, Yankee Doodle’s Pony, God Bless America, and Let’s Hear it for America. Each song was introduced by a student explaining the song’s significance as part of our patriotic heritage. It was a lovely afternoon, and the students (particularly our granddaughter) did a great job. I found it interesting --- and appropriate --- that they noted those three days, and it got me wondering if anyone had discussed the lyrics of the songs with the students --- or provided any historical background as to when they were written, etc. When I questioned our granddaughter about it, she said they had talked about it a little, but not much. No surprise there --- the concert was about entertainment, not a history lesson. And certainly, I remembered learning some of those songs as a boy. I surprised myself recalling lyrics to songs I recognized from Jimmy Cagney’s Yankee Doodle Dandy movie--- the Hollywood version of George M. Cohan’s life. But, more deeply, I looked at how young these children are and how “patriotism” is superficially indoctrinated into all of us (and I certainly don’t believe the U.S. is the only place this happens). When I was teaching, I often used Socratic Seminars as a teaching strategy. For those unfamiliar with the Socratic Seminar process, here’s an explanation from the Facing History and Ourselves project: A Socratic Seminar is a method to try to understand information by creating a dialectic class with a specific text. In a Socratic Seminar, participants seek deeper understanding complex ideas in the text through rigorously thoughtful dialogue. This process encourages divergent thinking rather than convergent. In a Socratic Seminar activity, students help one another understand the ideas, issues, and values reflected in a text through a group discussion format. Students are responsible for facilitating their group discussion around the ideas in the text; they shouldn’t use the discussion to assert their opinions or prove an argument. Through this type of discussion, students practice how to listen to one another, make meaning, and find common ground while participating in a conversation. The “text” of a Socratic Seminar can be a piece of writing, a recording, a snippet of video ---- anything that provokes thought and requires analysis. Seminars are a wonderful method for probing deeply and looking for the “truth” of a text. The text I would often use to introduce teachers (at workshops/conferences) or students (in classes) to the method was The Pledge of Allegiance. What I discovered, not surprisingly, is that, while most folks can recite The Pledge, very few had ever taken any time to examine what it is they are saying. And I believe that’s true of the songs the Third Graders were singing. The overall sense we get from the words of these patriotic texts (whether songs or the pledge) is that America is a wonderful place, the “home of the free and land of the brave.” What I would contend, though, is that this subtle, unconscious indoctrination promotes a blind --- and, yes, thoughtless --- nationalism that is often mistakenly called “patriotism.” And I think it’s worth taking some time to examine the difference between those two concepts and how we need to encourage students --- as well as adult citizens --- to examine what we’re singing/saying when we’re asked to “stand and honor America.” The definition of patriotism is: “the feeling of love, devotion, and a sense of attachment to a country or state. This attachment can be a combination of different feelings for things such as the language of one's homeland, and its ethnic, cultural, political, or historical aspects.” By contrast, nationalism is: “identification with one's own nation and support for its interests, especially to the exclusion or detriment of the interests of other nations. “ It’s important to note that patriotism is an “attachment” to your country and may well include “feelings for” its ethnic and cultural characteristics. Nationalism, in our current context, not only means the “exclusion or detriment . . . of other nations” but also includes many current U.S. citizens (or immigrants) originally from “other” nations. The Christian Nationalism that dominates the MAGA Republican party is markedly exclusive and promotes the “detriment” not only of other nations but also any citizens who may have hailed from those nations. It is important to call this out --- this is definitely NOT patriotism. The connection between what MAGA claims as “patriotism” and those adorable Third Graders singing patriotic songs is that the MAGA nationalists simply apply the superficial words from those songs (or the Pledge) and claim it’s “patriotism” when, in fact, it is a hollow and self-serving claim. The MAGA cult believes “liberty and justice for all” only applies to white Christian nationalists --- those they see as “true” Americans. Listen to Trump’s railing about “vermin” and immigrants “poisoning the blood” of the country and the MAGA notion of “patriotism” is clearly a form of “nationalism,” aimed at the “exclusion or detriment” of the “Others” (Black, Brown, Yellow, Red, et al) in our nation. The MAGA cult will glibly cite phrases reminiscent of the songs the Third Graders were singing --- with the possible exception of “This Land is Your Land” because, clearly, their belief is that “This Land is MY Land.” The next time you are asked to stand to “Honor America,” please remember to actively listen to the lyrics being sung --- and connect them to our nation’s history. I don’t find “The Star-Spangled Banner” to be (musically) very inspiring but when I actively listen to the lyrics, the story is quite compelling --- and the Battle of Fort McHenry is vividly depicted. I don’t like the way MLB, since 9/11, has jingoistically asked us to “Honor America” during the 7th inning stretch but, again, if you actively listen to the words (“and crown they good with brotherhood”) the appeal is to patriotism, not nationalism. The second verse of “American the Beautiful,” by the way, notes “Confirm they soul in self-control/Thy Liberty in Law!” A nation of laws, not men --- which is what true patriots, not phony nationalists, will have to defend this November by turning out the xenophobic, racist MAGA cult once and for all. Then and Now

I noted in late January that I was back in the classroom. It was familiar and revelatory at once. Teaching for me has always been a fish-in-water situation --- it’s a natural (essential)condition. But it had been ten years. A decade. Here are some facts from the year I retired:

There are some “the more things change” events there, but also quite a large portion of “Oh, yeah . . . I forgot about that . . .” On the cultural scene, it was:

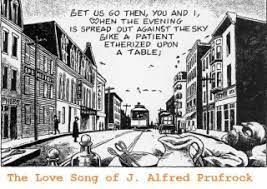

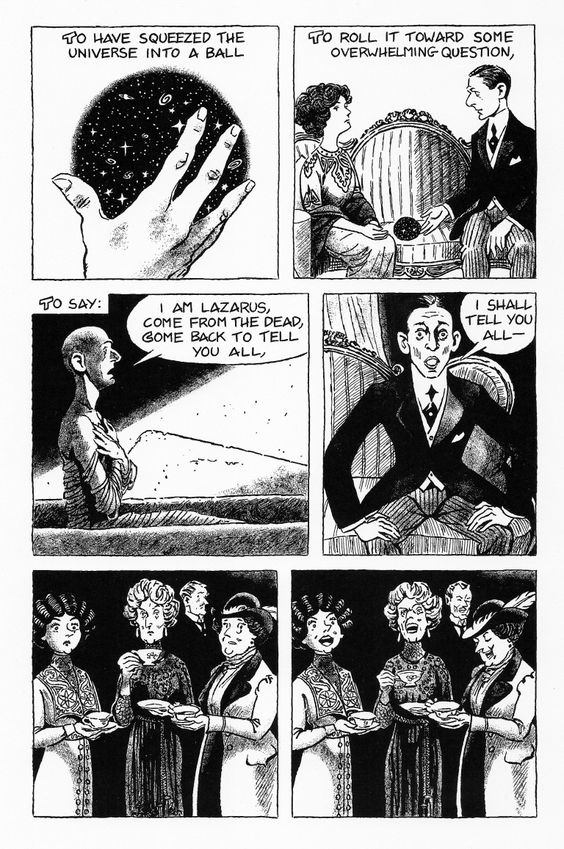

The students I worked with this semester were 8,9, 10 years old at that time. When I was that age (8,9,10): Sputnik had just been launched, those San Francisco Giants were just leaving New York for the West Coast (along with my family’s beloved Brooklyn Dodgers) and Dwight Eisenhower was President (with Richard Nixon his Vice President). That reflects just the tip of the iceberg “gulf” between me and my students. And now it’s May 13th and the semester is over. As an educator, there’s always a question about “What am I learning?” or “What did I learn?” The answer, at the end of this semester: quite a bit. But it’s not easy to relate quickly. Time is needed to reflect, cogitate, sort through, and relate. My impulse is to turn to T.S. Eliot and Prufrock --- so I’ll pull on that string and see what unravels. As with every class I’ve ever taught, I read The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock to this class. And, as with every class I’ve ever read it to, I explained that I first heard it in 11th grade when it was read aloud to me (and my classmates) by Lester Faggiani, my high school English teacher. Mr. Faggiani had been an actor before becoming a teacher and his dramatic reading of Prufrock was exhilarating and inspiring --- and every time I’ve read it to a class I have tried, as best as I could remember, to imitate Mr. Faggiani’s version of the poem. Hearing it aloud, as I read it, remains an exhilarating and inspiring experience for me (if not, necessarily, for my students). After Mr. Faggiani’s dramatic rendition, first heard in the spring of 1966, we spent days analyzing the poem --- and each day was a revelation to me. Always interested in poetry, Mr. Faggiani’s reading and careful guidance through the stanzas, not only accelerated my desire to learn more but kick-started my writing life --- as a poet! So, reading Prufrock to this class, this Spring released a revelatory weight I’d been unconsciously carrying since early February. Eliot’s words resonated with greater power than ever before --- and not just the “I grow old, I grow old” phrase. Eliot starts Prufrock with that wonderful invitation: “Let us go then, you and I, when the evening is spread out against the sky . . .” before he levels you with “like a patient etherized upon a table.” Can you imagine a more brilliant start for a poem about an elder reflecting upon his life? It’s sunset and there is a person in the twilight of consciousness, etherized, that state of being alive yet so close to . . . not . . . . As I stood before these vibrant, talented, energetic students I vividly remembered being their age --- and was also strikingly conscious of my current age. At once, I could see them absorbing Prufrock’s story --- his dilemma ---and appreciating the artistry of Eliot, yet never thinking they, like I, might someday become Prufrock themselves. It was a teachable moment for me! It conveyed the weight of the poem as it never had before --- and that was simply after reading the first lines. We continued. Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets, The muttering retreats Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels And sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells: Streets that follow like a tedious argument Of insidious intent To lead you to an overwhelming question ... Oh, do not ask, “What is it?” Let us go and make our visit. Eliot again beckons (“Let us go . . .) and we follow, of course. For me, the image of cheap hotels and sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells were recognizable images. Having grown up on the South shore of Long Island, in a town where summering New Yorkers caught ferries to go to Fire Island, I was all too familiar with the hotels (motels, more often) and sawdust-covered floors of seafood restaurants. My students, less so, given their far-flung and diverse hometowns (in Colorado, Missouri, Virginia, California, Georgia, etc.). The real focus in this stanza is on the wonderful assonance of tedious and insidious and being led to an overwhelming question --- one which is not confronted until the last stanzas of the poem/journey. So, there we are, somewhere near a waterfront in our etherized state and Eliot jump-shifts to some women (at a museum?) before bringing us back to those streets --- now as a cat. The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the windowpanes, The yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the windowpanes, Licked its tongue into the corners of the evening, Lingered upon the pools that stand in drains, Let fall upon its back the soot that falls from chimneys, Slipped by the terrace, made a sudden leap, And seeing that it was a soft October night, Curled once about the house, and fell asleep. Providing us with a familiar image (a cat), Eliot introduces the eerie “yellow fog” and “yellow smoke,” continuing Prufrock’s journey into a world he has not known. This is a journey my students are just beginning, one which may (or may not) present them with “unknowns” that will challenge, overwhelm, or fall by the wayside. Looking back, it’s easy to recount my own --- but not something I need to share with them, not while we’re engaging with the energy of this poem. The next stanza requires more immediate discussion and reflection. And indeed there will be time For the yellow smoke that slides along the street, Rubbing its back upon the window panes; There will be time, there will be time To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet; There will be time to murder and create, And time for all the works and days of hands That lift and drop a question on your plate; Time for you and time for me, And time yet for a hundred indecisions, And for a hundred visions and revisions, Before the taking of a toast and tea. It is only in your old age that you realize, if fact, how finite time is. For my students there will be time ahead --- and this is the significance of reading Prufrock now --- at least that’s why I thought they should hear it and reflect on it now. They are only beginning their journey of preparing “a face to meet the faces that you meet” and, as actors, singers, and dancers, especially so! Ah, but “time to murder and create.” Again, as artists, “creating” is their natural inclination but the need to “murder” --- to edit, revise, to dismiss ideas you love --- ah, there’s the challenge. How will they respond to those “questions” dropped on their plates? And what about those “hundreds (of) indecisions/And for a hundred visions and revisions?” Eliot/Prufrock is foreshadowing a young person’s future while reflecting on an old person’s history. And, after confronting the reader with those ideas, Eliot heads back to the ladies in the museum --- where, perhaps, they are “taking of a toast and tea?” But the journey, like time passing, persists. Prufrock reflects that “indeed there will be time” for wondering (“Do I dare? and, Do I dare?”) but, most significantly, turning back and descending the stair. The irony of J. Alfred Prufrock’s “Love Song,” of course, is that, as we read on, we discover: I have seen the eternal Footman hold my coat, and snicker, And in short, I was afraid. We are given a series of episodes in Prufrock’s life between his descending the stair and the Eternal Footman’s snickering that account for his fear: his thinning hair and body, his concern with disturbing the universe, his wondering about making decisions and indecisions --- as well as measuring one’s life in coffee spoons. Prufrock has experienced women saying “That is not it, at all. That is not what I meant, at all.” Prufrock has recoiled at the eyes that fixed him “in a formulated phrase,” leading him to wonder, again and again, “how should I presume?” He wonders if “it” would have been “worthwhile” to pursue any number of actions or paths --- or make decisions --- that would have altered his personal trajectory. And that’s what leads him to admitting his fear as well as leading us to answering the first stanza’s “overwhelming question.” When Prufrock exclaims: No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be; Am an attendant lord, one that will do To swell a progress, start a scene or two, Advise the prince; no doubt, an easy tool, Deferential, glad to be of use, Politic, cautious, and meticulous; Full of high sentence, but a bit obtuse; At times, indeed, almost ridiculous-- Almost, at times, the Fool. We all know Hamlet’s famous question: To be, or not to be . . . that is, indeed, the question. And here is Prufrock, not only claiming he is not Hamlet but describing himself in a series of damning descriptors, culminating in his vision of himself as the Fool. The irony and impact of this “Love Song” is completed when Prufrock shares with us that he has not only heard the mermaids “singing each to each” but that he believes “I do not think that they will sing to me.” The final image of watching those mermaids “riding seaward on the waves,” moving away while he has “lingered in the chambers of the sea” and drowns is, at once, dramatic and tragic. In discussing this poem with enormously talented and energetic young people embarking on their lives and careers, Prufrock, hopefully, serves as a brilliantly woven cautionary tale. Reading it as a septuagenarian, it provides a balance sheet against which one can assess their own journey. As a poem I have visited and revisited throughout my life, this recent reading --- particularly sharing it with this group (all born this century!) has had a powerful impact upon me. The students were, by my measure, suitably impressed with Eliot’s artistry as well as his wonderful imagery and command of the language. It’s hard to know how much power the message had, in the moment. The hope is they will return to Prufrock as they progress in their careers/lives and consider their own “decisions and revisions.” My take, starting with Mr. Faggiani’s reading in 1966, is that Prufrock inspired me on several levels. It’s imagery and language captivated me as a high school upperclassman but it’s message, over time, provided genuine guidance. I believe throughout my life there was an unconscious or subconscious voice always reminding me not to feel as Prufrock does when my “arms and legs are thin.” Indeed, as I reflect on the years between my introduction to J. Alfred and my most recent encounter, I can honestly say I won’t wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled and I will dare to eat a peach. To borrow from another favorite poet, Prufrock’s Love Song “has made all the difference.” Trump Trial, Larry & Teresa, & Cabaret! Another week has flown by and, beyond the inordinate amount of April showers, it was another busy one for these two inhabitants of Winnipauk Village in scenic Norwalk, Connecticut. The first criminal trial of a former U.S. President began in earnest on Monday, with the entire jury selected by the end of the work week. On Wednesday evening we traveled to the Fairfield Theater Company’s StageOne venue to hear wonderful, original Americana music created by Larry Campbell and Teresa Williams (https://www.larryandteresa.com/), and then, on Friday, we went to Bridgeport’s Downtown Cabaret Theater to see a stunning production of Cabaret by my Norwalk Conservatory of the Arts students. All of this created quite a bit to ruminate about as we headed into the homestretch of April. Last week, with O.J.’s passing, we considered the late-20th century “Trial of the Century.” This week, we’re confronted with our first “Trial of the Century” in the new millennium. The importance of the trial cannot be understated. Despite what various media outlets may say --- that it’s “only” about hush money payments and it’s “barely” a felony --- the fact of the matter is this trial is about trying to influence the outcome of a Presidential election (2016). While I don’t believe Trump will actually do jail time if he’s convicted, the importance of this man being made to adhere to the rule of law is really what is most important about this trial. Make no doubt about it, Donald J. Trump, the presumptive Presidential candidate for the Republican Party, is an aspiring autocrat with clear fascist dictator designs. I would only remind people that “good Germans” in the 1920’s, seeing Italy’s turn toward fascism, believed “it can’t happen here.” That Trump is already Putin’s “useful idiot”, and we have a clutch of pro-Putin people in the U.S. Congress only exacerbates the potential crisis we’re facing. 200 days out from the 2024 Presidential Election, the citizens of this country need to recognize Trump is neither a “populist” nor a “patriot” --- that his appeal is, in fact, quite similar to that of the 20th century fascists, pitting groups of people against each other based on race, religion, ethnicity, etc. and recruiting supporters who believe they, somehow, have been shortchanged by “the system.” All the while, of course, Trump and the super-wealthy who support him are the only “winners” with this calculus. And the remainder of our week --- gathering with other people to hear music and watch musical theater, only made the Trump Trial resonate with greater intensity. Larry Campbell and Teresa Williams have been playing music together since the 1980s, originally as country/western oriented artists but evolving into what has become known as “Americana” or “Roots” music --- a combination of country, folk, R & B, blues, and bluegrass. Campbell is a stunningly accomplished multi-instrumentalist, playing the guitar, pedal steel guitar, the violin, the mandolin, and slide guitar. He also is a gifted vocalist and has played with an impressive list of musicians, not the least of whom is Bob Dylan (from 1997 to 2004). Campbell also produced two Grammy-winning Levon Helm albums. Teresa Williams is an accomplished vocalist who, when not playing with Campbell, has supported an array of acts across genres. What is most compelling about their shows (and we’ve seen them many times now) is how self-effacing and charming they are. (check this out: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wv1dpPeeVVo) Seeing them again on Wednesday not only reminded me how impressive and talented they are but also made me acutely aware of how important people gathering together to appreciate other (generally more talented) people creating art in your presence is. That these particular artists’ milieu is “Americana” seemed poignantly relevant midweek during the Trump trial. During the performance I couldn’t help but reflect on this idea that people, humans, have gathered together to watch and listen to other people make music, or perform plays for longer than we can accurately pinpoint. As important is the idea behind it all --- that the art that is being witnessed is special, unique, out of the ordinary --- and worth one’s time. It elevates, it exhilarates, it excites --- and it evokes a spectrum of emotions. I couldn’t help but compare this serene yet stimulating gathering, focused on four musicians creating art we hadn’t experienced before, with the over-the-top rallies Trump (who is on trial!) conducts around the country ---- like some kind of traveling Tent Revival revue. Gathering to listen to music in hope of achieving some sense of the Hindu dharma, hoping for some insight into ourselves and our world, could not stand in higher relief to the Clown Car that Trump rallies are. And I was struck by how, watching this “Americana,” it stood in stark contrast with Trump’s flag-hugging claims of being a “patriot.” And that became all the more striking when, on Friday, we went to see Cabaret. Cabaret began its Broadway run in the fall of 1966 and won two Tony Awards in 1967. In the fall of 1967, I was a college freshman and hadn’t ever seen a Broadway show (I remember my mother went with her “girlfriends” --- to see A Funny Thing Happened . . . , Fiddler on the Roof, etc. in the ‘60’s . . . but I never was “invited” to join her). As luck would have it, in October of ‘67, a fellow freshman football player, Eric Klosterman, knew I was a Joe Namath fan (despite being a lifelong NY Giants fan) and asked if I’d like to see a Jets game at Shea Stadium with him. Eric’s “Uncle Don” worked for the Houston Oilers, so we could go in for Saturday night and see the game on Sunday, courtesy of “Uncle Don.” Only after taking the New Haven railroad into New York and finding our way to the Summit Hotel did I learn that “Uncle Don” was the General Manager of the Houston Oilers and we’d be staying with him in a suite. After ordering “whatever you want” from the Room Service menu, “Uncle Don” asked if we wanted to see a show and, when we said, “sure,” he called downstairs and told us there were tickets for Cabaret (one of the hottest shows on Broadway at that time) waiting for us at the Concierge Desk. I got to see Joel Grey and Lotte Lenya in what was, at that time, quite an “edgy” musical ---- particularly in its dealing with homosexuality and abortion. Indeed, the Kit Kat Klub was a den of iniquity --- and the presentation of the slide from Weimar Germany into Nazi Fascism was chilling, too. Remember, the parents of our generation had fought in WW II against the evil of Hitler and his minions. What I realized last night, as I watched my students from the Norwalk Conservatory impressively perform the show, was that those students are the same age (now) as I was when I first saw the show! That led me to wonder if they at all recognize the fascism they portrayed in the musical is, indeed, a reality we are facing in our society and in the Presidential Election. Despite their youth, the students presented a marvelously mature rendition of the show on all levels --- singing, dancing, acting like genuine professionals. And it led to my reflecting, again, on this uniquely human endeavor --- creating art. In this instance, there was a genuine sense, on my part, that “everything old is new again.” Homosexuality? Abortion? Fascism? These are all hot-button political issues in the 2024 election, with the forces of fascism and their opposition to same-sex marriage and LGBQT+ rights and their rejection of women’s rights (particularly regarding abortion) are paraded as “patriotic” and “truly American.” Cabaret shines a direct light on the lie of “it can’t happen here,” as Herr Schultz is convinced, despite being a Jew, that he is safe from the Nazis because, after all, he is “a German.” In the “America” that Trump and his allies want to create, only those who buy into the narrow, pro-Putin, bigoted view of the United States and the world are “safe,” reinforcing the importance of the trial being conducted in lower Manhattan. And that takes us full circle. It’s important for every citizen who cares about the future of our country to pay close attention to this, the first of several, trials Trump will face. He is running to stay out of jail and create an American society where he (and his ilk) are insulated from the rule of law. As bad, in the kind of world Trump would promulgate --- one where artists like Larry Campbell and Teresa Williams and my students from the Norwalk Conservatory would not be free to present their works in those communal settings we love to attend. Keep in mind what “art” became under Hitler and Stalin --- a vehicle for state propaganda and revisionist history. Those are the choices on the ballot this November and it is imperative that concerned citizens make sure they --- and their fellow citizens --- make informed choices to guarantee freedom and the rule of law remain cornerstones of our democratic republic. O.J., Jon Stewart & A Hawk at School It’s Friday, April 12th, the conclusion of week that saw the passing of O.J. Simpson, a performance by Jon Stewart at the Palace Theater in Stamford, and my Thursday English Composition Class at the Norwalk Conservatory of the Arts being interrupted by a red tail hawk. Weaving those disparate events into a culminating reflection is an appropriate writing challenge in the wake of the solar eclipse and earthquake. What can be written (or said?) about O.J. that hasn’t already appeared somewhere? He was an almost constant presence on the American cultural scene from the late 1960’s until the turn of the century --- and then, periodically, like Halley’s Comet, reappeared. O.J.’s evolution from Heisman winning, NFL record-setting football star to omnipresent pitchman, sports analyst, and movie “star” appeared to be a wonderful American Dream crossover story(successful Black man appeals to White audiences). As Nelson George noted: To a great degree O.J. showed a pathway to black athletic crossover success that was followed quite explicitly by Magic Johnson and Michael Jordan. The world O.J. lived in was a seductive one, a place of inclusion where you could make serious money by making white gate keepers comfortable and not offering too many aggressive arguments for black empowerment. Simpson steered clear of racial politics and civil rights activism (he was quoted saying, “I’m not Black, I’m O.J.”) but all that changed with “the trial of the century” that ensued after Simpson was charged with a double murder in Los Angeles in the fall of 1994. What we couldn’t have realized in the moment --- in that pre-social media world --- was that from the beginning of that white Ford Bronco being chased in slow motion up Highway 5 in L.A., a new cultural/media world was emerging --- on the cusp of the technology and dot.com revolution. O.J.’s car chase and eventual trial created the appetite for what has become a seemingly endless variety of Reality TV offerings on broadcast, cable, & streaming platforms. That O.J.’s personal lawyer and confidant was Robert Kardashian is more than ironic in retrospect. The groundwork for all the CSI shows & their ilk was also spawned during that trial, with use of DNA evidence and forensic science playing a prominent role in the proceedings. And, particularly significant in this election year, was how O.J.’s lawyer, Johnnie Cochran, brilliantly manipulated the media and the jury into seeing Simpson as the victim of a corrupt police and judicial system! Keep in mind, the Rodney King L.A. riots were fresh in peoples’ memories. Long before everything went viral, there were very few citizens who had not seen the horrific beating King suffered at the hands of eight police officers, along with their hideous racial slurs about King. The L.A. police department, led by Daryl Gates, was notoriously corrupt and racist --- a factor that played directly into Cochran’s defense of Simpson. As CNN noted: “Simpson took on a new role: He became a stand-in for Black people who had been railroaded by the justice system.” When the jury found Simpson innocent the cavernous fault line that exists between White and Black America revealed itself, as Blacks applauded the verdict over the racist justice system and whites saw it as a travesty, setting a murderer free. In that moment, there was little reflection about what O.J. represented for the Black community --- and that was not simplistic. Here’s a Black man of means, a celebrity --- one who could afford to hire a team of lawyers who were the best at what they did and who could, as those same lawyers did for so many wealthy, privileged white clients --- get their client off. And the prosecution, for their part, fumbled the ball at every opportunity. Worse, the L.A. Police Department botched almost every aspect of evidence collection. Barry Scheck, a classmate of mine at Yale and co-founder of the Innocence Project, the pioneering group in using DNA technology, was hired by Simpson’s team, and told me that the contamination of all the evidence in the case, not just the DNA, made it impossible to unequivocally declare Simpson guilty. The Simpson legal team was able to construct a narrative of “alternative facts,” leading to O.J.’s acquittal. We’re familiar with “alternative facts” and “victimization” being used by politicians today, of course --- and particularly by Donald Trump. It’s reported that Barack Obama said: “Trump is for a lot of white people what O.J.’s acquittal was to a lot of Black folks ― you know it’s wrong, but it feels good.” And that certainly seems to be the case. As we witness the passing of Simpson, a few months shy of his 77th birthday, we should reflect on what a watershed moment his trial was in our cultural history --- and how much of what’s commonplace today, began 30 years ago. That O.J. was only two years older than I at his passing gave me pause, too. It feels too soon, even if he wasn’t a good person. I certainly have noticed I spend more time thinking about mortality these days --- and that was brought home when we went to see Jon Stewart at the Palace Theater in Stamford on Wednesday night. Stewart was wide-ranging and thoughtfully entertaining throughout his (approximately) 75-minute stand-up routine, which started with his reflecting on his own age and noting that he was, at 61, “old.” My immediate reaction was, “Hey, that’s nothing,” but his insights were accurate and certainly hit home. For instance, upon visiting his doctor because of a shoulder “issue,” he asked why his hair had turned white. The doctor’s explanation was straightforward: basically, your body stops producing melanin for your hair. As Stewart noted, it apparently transfers the color to a “new series of irregularly shaped moles all over my body.” As for his shoulder, the rotator cuff is torn (a problem the Lovely Carol Marie shares). Asking whether it could be operated on, the doctor politely sidestepped the issue and asked questions about Stewart’s “reach frequency” --- in other words, “How often to you really need to reach in such a way that is too painful?” Basically, the doctor was telling Stewart what many of us have heard recently: “There’s really no point in operating on someone your age --- there will probably be more complications than benefits.” Stewart, in his inimitable style, translated that as: If I take my car to my mechanic and he discovers that transmission is shot, he doesn’t say, “How do you feel about walking? Yet that is where we, as Senior Citizens, are. It’s a twist on an old adage: “If it’s broke, don’t fix it.” It’s part of this cycle, of course, so I have to accept and integrate into my own thinking that O.J. Simpson, who was in college at the same time I was, has passed on. From this point on, who knows? And that life and death theme presented itself to me in a more concrete way on Thursday, while teaching in downtown Norwalk. The room I work in is a large open space --- suitable for dancing, yoga, performing one-act plays, and, oh, yes, teaching English Composition. We are above a branch of the Fairfield County Bank and have wonderful (almost) floor to ceiling windows that overlook Wall Street. Those windows provide excellent natural light on sunny days and even on overcast afternoons, like yesterday, still illuminate the room nicely. As we were beginning to discuss Strindberg’s short one act play, “The Stronger,” one of my students excitedly pointed to the far window and exclaimed: “Look, a hawk!” at which point we all jumped up, grabbing for our phones, and proceeded to spend the next 5 minutes or so photographing a good-sized red tail hawk who was sitting on a street light pole that had a “Norwalk Conservatory of the Arts” banner suspended on it. It was fun and I began knocking on the window to get the bird’s attention (he seemed to look at us a bit) until he finally decided to take flight --- at which point my students (who are all 18, 19, 20 years old) ran along to see him fly by the other two windows. In all, a wonderful moment. When we re-grouped, before returning to Strindberg, I related to the students how this incident reminded me of James Herndon’s book How to Survive in Your Native Land. Chapter VI is entitled: A Dog at School and it opens with this paragraph, plus: Dogs often wander into the classrooms at schools and always cause an up uproar. Kids cannot contain themselves when dogs appear in the midst of an Egypt lesson, for what reason no one seems to know. Why couldn’t they, the kids, just let the dog be in the class, wandering around, sniffing here and licking a few hands there, quietly moseying about in the style of dogs while the class continued with the most important part of the lesson on Egypt? But no, they can’t. They got to rush the dog, they got to pick him up and drop him, they got to offer the dog candy and pieces of sandwich, they got to yell and scream and act like they never saw any dog before in their whole lives. So the teacher then got to say Get that dog out here! (saying later in the teachers’ room, I don’t mind the dog, I even got a dog at home and like dogs, and if those kids could just have the dog in there without all that fussing during the crucial lessons about Egypt when I just got to get it over to them, what’s the problem? Haven’t they ever seen a dog before?) and nine kids just got to chase the dog around until the teacher got to grab the dog herself and throw the dog out and shut the door and then argue with the kids about the dog in the room (if you could just have the dog and not have to make such a commotion, she says to them, trying to explain, not wanting to be some kind of monster, hating dogs, while all they want is that dog). What’s it all about? Well, of course, that dog is alive, and old Egypt is dead. (pp.52-53) For those who don’t know me, you haven’t been subjected to my going on and on about Herndon and How to Survive. I own a “second printing” hardback edition that was published in 1971, the Spring of my Senior year in college and it is the book that set my course to teaching. There are very few personal items that have survived the 53 years since I first read this book, but the fact that it was what sprang to mind as my students (and I) rushed to the window yesterday attests to the enduring power of the written word. And it also brings me full circle in this reflection. The hawk is alive, and Strindberg is dead (though the students did get back on task and did a fabulous job analyzing and re-imagining the play, replete with directorial and acting choices/decisions) and I recognized that, in fact, I am teaching my final class. While I love the students and believe they have bright futures in singing, dancing, acting, directing, etc., I am too much of an academic (and I can’t believe I’m saying that) for this place to be a “good fit.” Beyond that, though, I’m about to celebrate the 75th anniversary of my birth and years ago, when preparing teachers in Brown University’s M.A.T. program, I often noted that “Teaching is a young person’s game.” It is. And I’m not. There’s a fleeting image of Willie Mays in a Mets uniform, stumbling forward and not catching a routine fly ball. I hear Willie whispering, “Don’t stay a season beyond your career.” I’m glad I gave it a shot and it had its moments but, listening to Jon Stewart’s mechanic, I think I feel pretty good about walking. Stranger in a Strange Land

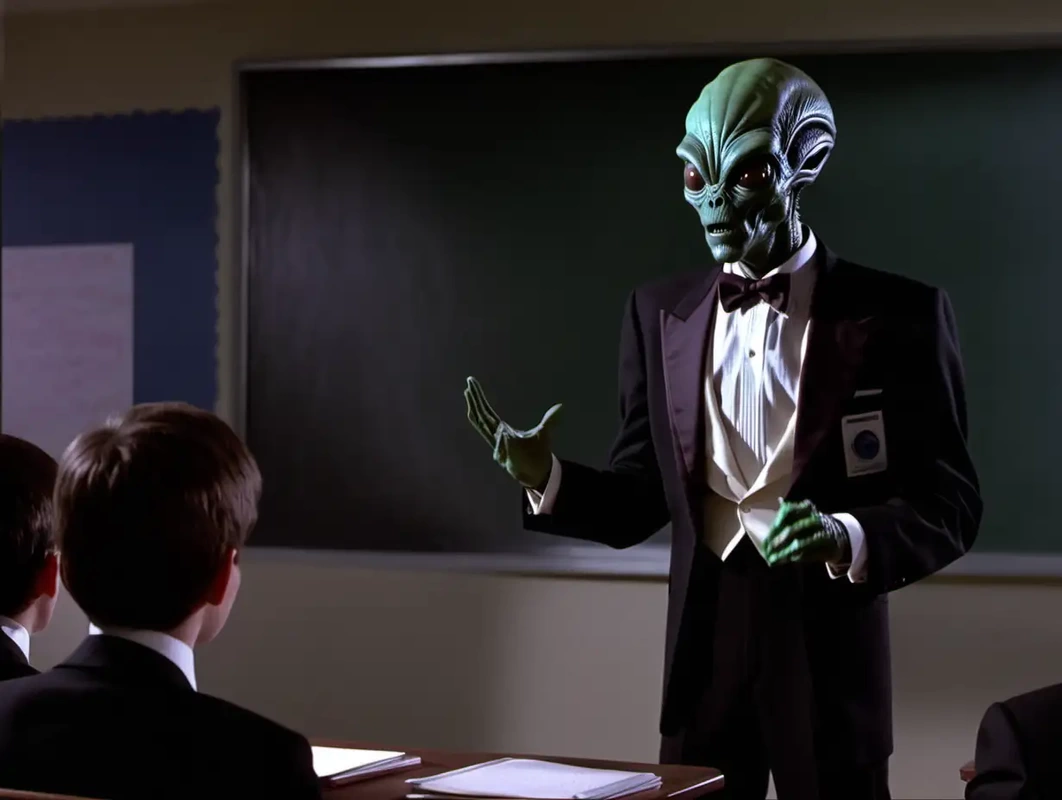

In the wonderful documentary “Going to Mars: The Nikki Giovanni Project” the poet likens the initial enslaved Africans --- kidnapped and sent to the American South --- much like humans meeting space aliens. I think the comparison is both brilliant and apt. Imagine those African people, ripped violently from their homeland, shackled, and transported on a vessel like none they had ever seen, by people unlike any they had ever encountered, and then deposited in an environment that was, indeed, “alien.” It conjures all those science fiction stories and urban legends where humans are abducted by space aliens and brought to a mysterious planet. This was, of course, only the first in a long line of traumatic experiences for those Africans. To think those scars haven’t been generationally transmitted would grossly diminish the disruption, the mental and spiritual damage, as well as the societal stigma that we all still live with. I talked about the Nikki Giovanni allusion while teaching this semester --- not only because the class was examining White Privilege and its presence in today’s world --- but also because, on a much smaller scale, I realized I had voluntarily enlisted to join an alien world --- but was slow to recognize it. We are now on Spring Break and I’m here to report on my experience on a mysterious planet --- The Norwalk Conservatory of the Arts. The Norwalk Conservatory of the Arts describes itself as follows: The Norwalk Conservatory of the Arts was founded in 2018 by industry creatives with the goal of creating a space that was equal parts training and opportunity. The Conservatory is comprised of a faculty of the greatest artists currently working in theatre and television. Located in Norwalk, Connecticut, our campus is in the backyard of the biggest theatre city in the world. We operate as a space where the artists of today can train, audition for professional work, and grow simultaneously. The conservatory built the LINK Program which developed into the full two-year conservatory that comprises NoCo today. With many alumni working on Broadway and on Television, a faculty of the most pivotal artists, close proximity to New York City, small class sizes, and a curriculum built for today’s industry, The Norwalk Conservatory of the Arts is Connecticut’s premiere training program for young artists. (website: www.thenorwalkconservatory.org) In December, 2023 I had seen a posting on Indeed that looked interesting. NoCo was looking for someone to teach English Composition to their freshman class. It was local and piqued my interest. I forwarded my resume and got a call to arrange a Zoom interview with the school’s Provost. That interview went swimmingly and, before I knew it, I had been hired to teach English Composition to college freshmen. But these were not your usual college freshmen because they had signed on to experience “a curriculum built to today’s industry.” And that “industry” was Musical Theater, Musical Theater Dance, and TV/Film Performance --- the school’s three curricular concentrations. What’s missing from that curriculum, of course, is “General Education,” which would include English Composition. It seems the school, in applying for accreditation as a legitimate State of Connecticut two-year, degree-granting college, had been informed late in the fall semester they needed to add “General Education” courses to maintain their accreditation and grant degrees going forward. Hence, the need to offer English Composition. As I write this, I’m not sure anyone else applied for the position. Nonetheless, while you may find it hard to believe someone three-quarters of a century old could be naïve, trust me, they can be --- because here I am. If I have a consistent flaw in my adult life, it is charging ahead without necessarily doing as much homework/research as I should prior to diving headfirst into a situation. This is well-chronicled in my memoir (Right Time, Right Places: One Teacher’s School Reform Journey, Adelaide Books, 2020) --- it’s right there in Chapter 30, The Worst Year of My Life. That story relates how I was so anxious to move back to New York City in 2008 I failed to complete my due diligence regarding where I would work or live --- resulting in not one, but two, disastrous experiences --- all in one academic year! Apparently, my 10 years in retirement didn’t bring any wisdom with it because, as the new academic semester got underway, I discovered that both my students and I had been rather seriously blindsided. Don’t get me wrong --- my students are wonderfully talented (some, I would daresay, are “gifted”) and energetic young people. They come from all over the country (only one in my class is from Connecticut) and bring with them a range of interesting histories and experiences. They all share one characteristic: they love performing and are clearly focused on carving out careers in the arts. Their days are packed with courses related to their goals --- acting, dancing, singing, yoga, etc. --- and they apply themselves to those studies with energy and enthusiasm. English Composition 101 less so. Much less so. And that was where the blindside came in. Most of the students signed on to the Norwalk Conservatory believing they would only be doing Arts-related classes, as well as attending auditions and working with “industry creatives” beyond what goes on at the school. Few, if any, thought they would have to take “General Education” courses, like so many they put up with in high school. I was unaware of this before meeting my first class in January. Blindsided. We started with 25 students (out of the 43 in the freshman class --- 18 “placed out”) in January. Now, in late March and on Spring Break, we’re down to 18. Several have “opted out,” choosing to make up the course at another point in time, while others have said they’re not particularly interested in attaining the A.A. degree but want to continue taking arts courses. The stalwarts who remain are resigned to taking the course, with several even engaging in the material with modest enthusiasm. For the most part, we’ve reached a place where we recognize this is not an ideal situation (for any of us, including the instructor) but it is something that has to transpire --- so why not make the most of it? I’ll spend some of my Spring Break preparing the final six weeks of the course, which includes a research project (I’ve already scheduled a “field trip” to the Norwalk Public Library, just down the street from the school). I’m also hoping to bring in a guest or two before the semester is over. I have several former students who have made careers in the Arts and could offer insights regarding the slings and arrows of the profession. In all, this experience is part of the growing pains of building a new school from the ground up. As “industry creatives” and not professional educators, the founders have rightly focused the school on creating an environment that provides students with maximum Arts preparation and opportunities, particularly given our access to New York City. “General Education is firmly, if uncomfortably, ensconced in the back seat. I’m here as an Alien, dispensing information that appears unrelated to the World my students live in and aspire to. Making English Composition 101 engaging remains the enduring challenge for the Academic Stranger in the “Industry” Strange Land.” Keep your eye out for the Final Report Card sometime in May to see how the students and the instructor co-existed throughout the Spring. Until then . . . . the story continues. The Legacy of the Roberts Court

There are 248 days until the 2024 Presidential Election. The primaries are proceeding but we already know the nominees. We also know the “Big Issues” that will dominate the news between now and November 5th. Rather than belabor any of that, I’d like to take a step back and note an item that may not be on everyone’s radar but should be. The Roberts Supreme Court has crossed the line. Their blatant right-wing activism should, once and for all, seal the legacy of this Court. Going back to the early 1990’s, comparisons between Roe v. Wade and the Dred Scott case were raised (by Antonin Scalia!), attempting to define what a Constitutional right to due process and privacy might be. I won’t belabor the arguments surrounding Substantive Due Process, but I will provide historical background on why I believe Dred Scott, Roe and now, the Dobbs decision, as well as the Roberts’s Court ruling kicking the Trump Presidential Immunity claim down the road, all combine to indelibly stain SCOTUS as an institution --- and endanger our democracy. For those who don’t recall their high school U.S. history course, the Dred Scott decision, handed down by the Roger Taney (pronounced Tawn-ey) Supreme Court in 1857 was a significant step toward Civil War. Here’s the Wikipedia summary: In March 1857, the Supreme Court issued a 7–2 decision against Scott. In an opinion written by Chief Justice Roger Taney, the Court ruled that people of African descent "are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word 'citizens' in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States"; more specifically, that African Americans were not entitled to "full liberty of speech ... to hold public meetings ... and to keep and carry arms" along with other constitutionally protected rights and privileges Taney supported his ruling with an extended survey of American state and local laws from the time of the Constitution's drafting in 1787 that purported to show that a "perpetual and impassable barrier was intended to be erected between the white race and the one which they had reduced to slavery". Because the Court ruled that Scott was not an American citizen, he was also not a citizen of any state and, accordingly, could never establish the "diversity of citizenship" that Article III of the U.S. Constitution requires for a U.S. federal court to be able to exercise jurisdiction over a case. Wikipedia also notes: The decision is widely considered the worst in the Supreme Court's history, being widely denounced for its overt racism, judicial activism, poor legal reasoning, and crucial role in the start of the American Civil War four years later. Legal scholar Bernard Schwartz said that it "stands first in any list of the worst Supreme Court decisions". A future chief justice, Charles Evans Hughes, called it the Court's "greatest self-inflicted wound" Scalia’s argument that the Roe abortion decision paralleled Dred Scott was primarily based on the concept that the Supreme Court, in both instances, had overextended its powers and was using an implied application of “citizenship” ---- and, therefore, the “right to privacy” associated with that “citizenship.” Scalia, of course, was quite intentionally trying to muddy the waters surrounding the Roe decision (somehow linking it to slavery) and the Court barely ruled (5-4) to sustain a woman’s right to control her own body. Therein lies the stronger comparison between Roe and Dred Scott. In supporting an extremely strict interpretation of the Constitution --- as conservatives and right-wing extremists are wont to do --- there is an overt desire to control the bodies of people who are, somehow, not equal to (White) Men. By issuing the Dobbs decision and tossing abortion back to the States --- knowing full well how many of those States would make it impossible for Women to gain access to the health care they need --- the Roberts Court clearly harkened back to the Taney Court, asserting the Supreme Court’s power to determine who controls the bodies of those perceived as “less than.” There are purported religious arguments regarding abortion, of course, but the Separation Clause clearly removes those arguments from the purview of the Court. Or, in the case of the Roberts Court, does it? With the addition of Trump’s three Roman Catholic Justices (Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, Barrett) joining three conservative Catholics already there (Roberts, Thomas, Alito), it appears the Court has taken an extreme turn away from the Separation Clause. Even if that is not the case, the Dobbs decision, overturning Roe (“established law” that Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett implied was inviolate during their confirmation hearings!), creates a clear parallel between the Roberts Court and the Taney Court, for all of history to see. And now, in providing Trump with exactly what he wanted --- a long delay for his January 6th Federal Criminal Trial --- the Roberts Court blatantly revealed their partisan colors. Given that Trump’s case --- that Presidents have total immunity from criminal charges (unless impeached and convicted by the Senate) --- is absurd, the Court’s decision is manifestly political. Trump lost the case in court, lost it (unanimously) in Appeal, but now, miraculously, the Roberts Court not only agrees to hear the case but also schedules Oral Arguments in late April, essentially guaranteeing that the trial, should it even begin in 2024, will clearly occur during this year’s Election Cycle. Even Judge Chutkan’s desire to start the trial as soon as possible cannot supersede the clear conflict conducting it during September and October would present. If this isn’t the nail in the Roberts Court Legacy, I don’t know what else one would need. All told, going back to Citizens United, it’s easy to document where the Roberts Court stands --- regarding individual rights vs. (dark) monied interests, Voting Rights, Affirmative Action and LBGQT rights (except for Obergefell/same-sex marriage ---- which Dobbs has now jeopardized!). This Court, historically, is on track to match the Taney Court as one of the most narrow-minded and bigoted in the history of the nation. Keep in mind, the Taney Court was operating in the middle of the 19th century! But that is, of course, where Alito, Thomas, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, Barrett, and Roberts are most comfortable. This all began with Ronald Reagan, of course, and his passionate animosity for the liberal/liberation movements of the ‘60’s and his “revolution” (more “devolution”) to un-do the strides made by minorities, women, gays, et al. It has taken forty-four years, but the Roberts Court is poised to catapult the society (against its will --- check the polling on Roe) back to that mythological immediate post-WWII period. That’s the “Great” America that Reagan, and then Trump, wanted to make again. The America of Joe McCarthy’s Red Scare, of Jim Crow segregation, of no rights for Women or LBGQT citizens as well as countless other minorities. The America where White, Christian men held power, set policy, and oversaw the world. Then, however, the Warren Court, the Civil Rights movement, the anti-War movement, the Women’s Liberation Movement, the Gay Rights Movement turned that old While Male world on its head. The ‘60’s and ‘70’s, when the United States was energized by movements aimed at (dare I say it) Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) became the “enemy” to an ever-threatened White Male Establishment (there, I’ve said it again!), requiring first Reagan, and then Trump, promise to “Make America Great Again.” You needn’t be a cryptographer to break that Code. And so, we now find that the Supreme Court, one of the three branches of our government created to protect our Rights, has thrown in with the MAGA crowd and is doing its damnedest to turn back the clock. And that’s why the Roberts Court will, historically, live in infamy, like the Taney Court. The United States survived the Taney Court (requiring a Civil War to do so, of course) and I’m hoping we will prevail over the Roberts Court, too. Defeating Donald Trump in November would do a great deal to cut the legs out from under this Court. If the other two branches are secured by politicians sympathetic to the Rights of all our citizens, laws can be passed, bills can be signed, actions will be taken to insure the citizens this court, as malignant as it is, cannot suppress basic freedoms and rights the Constitution guarantees. It will require action by the electorate, however, since the Court is doing all it can to insulate Public Criminal #1 from ever facing justice before November 5th. That action, along with Citizens United, Shelby, and Dobbs, will provide historians for debate fodder: which Court was worse, Taney or Roberts? That Art/Life Imitation Thing

|

|

- Home

- The Blast -Blog

- The Blast (Archive)

- Blast Directory (Archive)

- California Streamin'

- Politics

- Culture

- ART

- SONGS

- Reviews

- Op-Ed Material

- New Writing

- Old Writing

- ARCHIVES

- "If you went to Yale . . ."

- Outing the Privilege Gap

- Thoughts on TFA

- Sir Ken Robinson: Education & Creativity

- My 91 seconds of Rock-music-video Fame!

- Creating Democratic Schools

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Contact Info

Proudly powered by Weebly